AMR and the SDGs: aren’t we missing something?

Our winter blogs will all consider the Build Back Better narrative through the lens of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). CE4AMR’s PhD candidate Nichola Jones begins the series with an introduction to the Sustainable Development Goals and how these could become more AMR-aware. There are many goals where links to AMR are obvious, whilst the interplay of others is complex and indirect as Nichola explains….

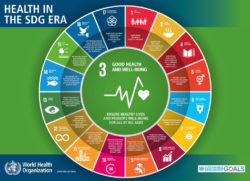

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), the naturally occurring process of bacteria becoming resistant to treatments such as antibiotics, is accelerating at alarming rates. This rise in AMR across the globe, and particularly in low-middle income countries (LMIC’s), is in part driven by the misuse of antibiotics in human and animal health. A UN General Assembly, held in 2016, acknowledged that AMR has the potential to impair gains already made in health, as well as impact future goals in health and beyond. Despite it’s urgency, AMR does not appear in most of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s): a set of objectives developed by UN agencies to improve quality of life across the globe by 2030.

Each of the 17 SDGs are underpinned by several targets, to guide policy makers in areas that span all aspects of our lives, including but not limited to: the climate crisis, universal health coverage, ending poverty and achieving gender equality. AMR has the grim potential to challenge most SDG targets but could reverse progress made in some areas. With that in mind, it is imperative that any attempts to ‘build-back-better’ should consider each SDG with an ‘AMR lens’ to unpack where we can improve our chances of progress. Unfortunately, AMR did not appear in any of the SDG’s until 2019 when the WHO added an AMR indicator to SDG 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing)  to monitor the rise in particular strains of resistant bacterial infections. Then a 2019 report from the SDG Knowledge hub described several opportunities to add AMR indicators into the SDG’s current targets so as not to over-burden already struggling health systems in LMIC’s.

to monitor the rise in particular strains of resistant bacterial infections. Then a 2019 report from the SDG Knowledge hub described several opportunities to add AMR indicators into the SDG’s current targets so as not to over-burden already struggling health systems in LMIC’s.

In a bid to ‘build-back-better’ after COVID-19, the APPG have provided a report that uses the SDG’s as a roadmap to improved systems in a post-COVID future. Given the potential impact of AMR globally, its’ absence in the SDGs and wider conversations about a better future is concerning. Existing indicators running through each SDG do map onto AMR challenges, however the language within the Goals does not explicitly mention AMR. As with the SDG Knowledge Hub report, it is possible to see where the wording of certain indicators could be tweaked to include AMR – without increasing expectations on already stretched resources in LMIC’s. Some examples are provided below, whilst over the coming months we will showcase guest blogs from various disciplines all reflecting on the challenge of incorporating AMR into the Build Back Better dialogue and SDGs. This blog will, therefore, present a non-exhaustive list of ideas on how to include AMR into several SDG targets and indicators.

SDG 1: No Poverty, and SDG 10: Reduced inequalities

The world bank predicts that an additional 28.6 million people will fall into extreme poverty by 2050, most of whom live in LMIC’s, as a direct result of AMR. This is because the rise in drug resistant infections will cause LMICs to lose around 5% of their GDP. In addition, we already know that AMR is also more likely to impact those that are the most vulnerable. Those in informal housing and slum communities, for example who have limited clean water and sanitation, co-habitat with animals, and cannot afford good quality health care.

Poverty impacts decision making at the individual, family and community levels as well as ultimately impacting policy decisions at the national level. Where individuals face out-of-pocket expenses when seeking health care (as is common in many LMIC’s) it is understandable that cheaper, but often inappropriate, options are preferred. This is particularly concerning with regards to AMR as using antibiotics when they are not needed, or mismatching drugs to bugs are key drivers of resistance. Whilst, across many LMICs access to antibiotics is a problem in itself, meaning people have little choice on how they treat infections. Target 1.4 of the No Poverty Goal states we need to improve access to basic resources for the poorest. This could be made AMR-aware by including access to basic health services that provide appropriate antibiotics and diagnostics to aid treatment. As the cost of treating AMR infections grows, those who struggle to access appropriate antibiotics, either because of growing out-of-pocket expense when buying antibiotics or geographical/infrastructure access issues, are undoubtedly more likely to be left behind. Target 10.1 of the Reduced Inequalities Goal monitors household income/expenditure and could be extended to monitor expenses relating to antimicrobials/infection treatments.

SDG 2: Zero Hunger, SDG12: Sustainable Consumption, and SDG15: Life on Land

A growing global reliance on farmed animal produce often encourages the use of antimicrobials (including antibiotics) unnecessarily. For example, as precautionary prophylaxis, in attempt to prevent illness before animals show symptoms, or as growth promoters to increase yield. Both strategies are dangerous because they employ broad spectrum antimicrobials before symptoms of disease are visible, and thus before diagnosis. In most cases infectious microbes won’t be causing the animal any harm, but antimicrobial exposure will increase the risks of mutations occurring to resist the drugs. As such resistant strains are likely to develop, and future infections will be more difficult to treat. Treated animals can pass antimicrobial residue in their waste, allowing resistance to develop in soil and water-based microbes in the environment, whilst consumption of these animal products can allow antimicrobials to pass up the food chain into humans.  A particularly concerning example of prophylactic use of antimicrobials occurs in South East Asia where the rapidly growing population increasingly relies upon cheaply available poultry. Producers use antimicrobials as prophylaxis to prevent infection at herd level, but this only drives the evolution of AMR whilst also passing antimicrobial residue up the food chain into human consumers. Responsible and sustainable farming practices are included in the targets for SDG 2; the term sustainable here could be extended to include rational and appropriate use of antimicrobials. Within SDG15 the treatment of food producing animals by antimicrobials could be considered within targets to protect animal welfare.

A particularly concerning example of prophylactic use of antimicrobials occurs in South East Asia where the rapidly growing population increasingly relies upon cheaply available poultry. Producers use antimicrobials as prophylaxis to prevent infection at herd level, but this only drives the evolution of AMR whilst also passing antimicrobial residue up the food chain into human consumers. Responsible and sustainable farming practices are included in the targets for SDG 2; the term sustainable here could be extended to include rational and appropriate use of antimicrobials. Within SDG15 the treatment of food producing animals by antimicrobials could be considered within targets to protect animal welfare.

SDG 4: Quality Education, SDG 5: Gender Equality, and SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

When considering education, children exposed to infections will need more time off school, thus compromising their learning. This will increase if the child’s infection is drug resistant requiring multiple trips to health facilities to source appropriate medication. The costs of health care and travel may then compromise the parent’s ability to fund the child’s education in the long term. Target 4.7 aims to promote sustainability through education, this could be extended towards the inclusion of AMR messaging and the need for appropriate and sustainable antimicrobial use.  However, the Quality Education Goal does conflate with the Goal of Gender Equality as in many LMICs female children are less likely to remain in school than males. This means any AMR messaging made through schools may miss the females in the population. Gender inequality in relation to health sees many men making the medical decisions for their wives and daughters. Where men are responsible for making these decisions, women can face barriers to accessing safe and appropriate treatment for any illness, including AMR infections. Target 5.6 relates to the need for women and girls to have access to safe reproductive health services. Indicators include the number of women and girls able to make informed decisions about their sexual health. This indicator could be extended to include the number of women able to make all medical decisions, including appropriate treatment for AMR infections, safely and independently.

However, the Quality Education Goal does conflate with the Goal of Gender Equality as in many LMICs female children are less likely to remain in school than males. This means any AMR messaging made through schools may miss the females in the population. Gender inequality in relation to health sees many men making the medical decisions for their wives and daughters. Where men are responsible for making these decisions, women can face barriers to accessing safe and appropriate treatment for any illness, including AMR infections. Target 5.6 relates to the need for women and girls to have access to safe reproductive health services. Indicators include the number of women and girls able to make informed decisions about their sexual health. This indicator could be extended to include the number of women able to make all medical decisions, including appropriate treatment for AMR infections, safely and independently.

Children and their parents also need to be supported to visit health care providers if they are unwell, schools often play an important role in the community to signpost people to appropriate and trained health care providers. However, this challenge extends to the workforce too. Growth can only be sustained in a future where workforces across the globe are safe from the threat of AMR. Where a country or region’s industry is primarily engaged in manual labor (as is common in LMIC’s) any communicable illnesses greatly reduce productivity at community, local and even national levels. Eligible workforces, and therefore capacity to grow, are greatly depleted when communities struggle to control communicable diseases, a problem extended when treatment for said illnesses are inaccessible, costly, and ineffective. Target 8.8 aims to improve working conditions and these indicators could be extended to include monitoring of infection rates in workplaces. Support also needs to allow workers to access healthcare including antimicrobials when necessary.

SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, and SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

While not immediately linked to AMR, people are only able to access appropriate medical treatments for infections when there is safe and reliable infrastructure. Where a community can easily access health treatments and maintain good hygiene practices, there is a positive impact on AMR. Communities living in slums, for example, are likely to experience high levels of infectious diseases due to lack of sanitation, poor food storage and preparation, sub-par drinking water and a lack of health services. Target 9.1 focuses on access to reliable and sustainable infrastructure, in particular monitoring road access in rural areas. This monitoring could be extended to include access to roads which lead to hospitals and other formal health services. SDG 9 also aims to promote scientific research, especially in LMIC’s, and could be extended to monitor/encourage research in AMR sectors.  Finally, target 11.1 focuses on improving slums and could be extended to include targets around infection prevention such as good drainage, and separation between human and animal dwellings. Such targets overlap with those of SDG6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) which sets specific targets around drinking water and sanitation. All targets discussed under SDG6 would have an impact on reducing AMR by reducing infection in the first place, thus reducing the amount of (unnecessary) antimicrobials used.

Finally, target 11.1 focuses on improving slums and could be extended to include targets around infection prevention such as good drainage, and separation between human and animal dwellings. Such targets overlap with those of SDG6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) which sets specific targets around drinking water and sanitation. All targets discussed under SDG6 would have an impact on reducing AMR by reducing infection in the first place, thus reducing the amount of (unnecessary) antimicrobials used.

SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions, and SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

Effective AMR response relies on the strong enforcement of regulations across multiple agencies. Target 16.6 aims to improve effective and transparent public services. These monitoring activities could be extended to include, for example, health institutions that control the distribution of antimicrobials. However, for AMR responses to be effective they must also bring together partners from across multiple sectors. The One Health approach considers the interlinkages between human, animal and environmental health and is steered by a tripartite alliance between the WHO, OIE and FAO. This group states an urgent need for partnerships that reflect the complex nature of AMR. Targets in SDG17 could thus be extended to ensure partnerships consider the One Health dimensions of AMR and encourage multi-agency cooperation.

Opinions expressed within this article are those of the author and are not necessarily representative of CE4AMR as a network. If you would like to contribute a blog or opinion piece regarding the inclusion of AMR within the SDGs or Build Back Better dialogue please contact Jess (j.mitchell1@Leeds.ac.uk).