Building Back Better through Creative Practice

Professor Paul Cooke who co-leads the CE4AMR network, discusses the use of creative practice and arts-based methods in the “build back better” narrative. Paul exemplifies these methods within a recently completed project and reflects upon the way they have helped understand the global challenge of AMR by using community knowledge. Participatory and arts-based approaches also generate outputs such as films, in the case of Paul’s example, which are valuable resources. Paul stresses the importance of analyzing these outputs to better understand the community you are working with, a process which could be critical during the “build back better” period post-COVID.

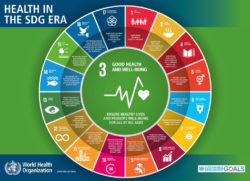

COVID has had a devastating impact on global health and finances, with its impact being disproportionately felt across the Global South. Before the pandemic, the International Institute for Sustainable Development, for example, identified an annual spending gap of one trillion Dollars, if we are to meet the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. This is clearly  set to be exacerbated by the costs of post-COVID recovery. If we are to ‘build back better’, the theme of this series of blogs, we will need to ensure, both, maximum efficiency in the way we deploy the limited resources that will be available to researcher and practitioners seeking to find solutions to the myriad other problems we face as a planet, and to ensure that make we understand the full value of all the resources that are available to us. With regard to AMR, one of these ‘resources’ is the range of knowledge that we can bring to bare on this problem. As an arts-based, practice oriented researcher, my work frequently involves working with communities in which a range of ‘actors’ wish to make a public-health intervention. Frequently, this is conceptualised either as a didactic process in which an arts practitioner might be brought in to produce a health campaign which can be tested out on a given community. Or a project might be developed to find out where the gaps around a particular problem in a community exist. If handled ethically, such approaches can be very useful. However, both can ignore the importance of particular knowledge about the question at hand that exists within a community, knowledge that is set to become evermore important in the resource-scarce post-COVID world we will be (hopefully) entering in 2021.

set to be exacerbated by the costs of post-COVID recovery. If we are to ‘build back better’, the theme of this series of blogs, we will need to ensure, both, maximum efficiency in the way we deploy the limited resources that will be available to researcher and practitioners seeking to find solutions to the myriad other problems we face as a planet, and to ensure that make we understand the full value of all the resources that are available to us. With regard to AMR, one of these ‘resources’ is the range of knowledge that we can bring to bare on this problem. As an arts-based, practice oriented researcher, my work frequently involves working with communities in which a range of ‘actors’ wish to make a public-health intervention. Frequently, this is conceptualised either as a didactic process in which an arts practitioner might be brought in to produce a health campaign which can be tested out on a given community. Or a project might be developed to find out where the gaps around a particular problem in a community exist. If handled ethically, such approaches can be very useful. However, both can ignore the importance of particular knowledge about the question at hand that exists within a community, knowledge that is set to become evermore important in the resource-scarce post-COVID world we will be (hopefully) entering in 2021.

One of the key starting points for the development of the the CE4AMR network was a project we ran in Nepal with our partners HERD International. Community arts against Antibiotic Resistance Across Nepal (CARAN)  used participatory video (PV) as a tool for developing community-level solutions to AMR. In recent years, PV has become an ever more popular tool in development contexts for supporting communities in low and middle income countries to raise awareness of issues that they do not feel are adequately represented in mainstream media. One area of growing interest in this regard is public health. However, PV had not previously been used to address AMR, currently considered to be one of the biggest public health issues we face globally.

used participatory video (PV) as a tool for developing community-level solutions to AMR. In recent years, PV has become an ever more popular tool in development contexts for supporting communities in low and middle income countries to raise awareness of issues that they do not feel are adequately represented in mainstream media. One area of growing interest in this regard is public health. However, PV had not previously been used to address AMR, currently considered to be one of the biggest public health issues we face globally.  Over the course of several months, we worked together to develop an intervention which used the WHO guidance on AMR to explore what two communities in Nepal considered to be the key barriers to the correct usage of antibiotics and supporting them to make a series of films that could help these communities to both reflect on ways to overcome these barriers, on the one hand, and to communicate their perspective to the policymakers responsible for developing and implementing the country’s AMR action plan. Throughout the project we focused on ensuring an equitable relationship between everyone involved in the project which respected, and valued, the distinct knowledge of all the different stakeholders involved. The project was careful to avoid the communication of any misinformation about AMR. However, equally important was understanding the specific experience of community participants.

Over the course of several months, we worked together to develop an intervention which used the WHO guidance on AMR to explore what two communities in Nepal considered to be the key barriers to the correct usage of antibiotics and supporting them to make a series of films that could help these communities to both reflect on ways to overcome these barriers, on the one hand, and to communicate their perspective to the policymakers responsible for developing and implementing the country’s AMR action plan. Throughout the project we focused on ensuring an equitable relationship between everyone involved in the project which respected, and valued, the distinct knowledge of all the different stakeholders involved. The project was careful to avoid the communication of any misinformation about AMR. However, equally important was understanding the specific experience of community participants.

Placing our project within the wider context of ‘participatory documentary’ practice, the project was particularly focused on understanding and valuing the world-view presented in the films the project generated, a dimension of such projects that is, somewhat curiously perhaps, often overlooked, with commentators tending to focus on the process of delivering PV, rather than the final products made.  Here we were interested in questions of power and how a close reading of the texts produced highlighted the complexity of the power relationships at work in these films, which, in turn, can allowed us to not only reflect in new ways on the processes at work in the project, but also to uncover both the particular complexion of gender relations and the role of young people in health-seeking practices when it comes to antibiotic misuse, dimensions that are have not been discussed enough in the literature on AMR. This new knowledge could not have emerged if we had not generated an ethos of equitable co-production across the project, a value that, as a recent article by Jessica Mitchell et al. notes, we see as central to CE4AMR.

Here we were interested in questions of power and how a close reading of the texts produced highlighted the complexity of the power relationships at work in these films, which, in turn, can allowed us to not only reflect in new ways on the processes at work in the project, but also to uncover both the particular complexion of gender relations and the role of young people in health-seeking practices when it comes to antibiotic misuse, dimensions that are have not been discussed enough in the literature on AMR. This new knowledge could not have emerged if we had not generated an ethos of equitable co-production across the project, a value that, as a recent article by Jessica Mitchell et al. notes, we see as central to CE4AMR.